Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde’s sermon on Jan. 21, 2025, by which she appealed to President Donald Trump to have mercy toward groups frightened by his position on immigrants and LGBTQ+ people – especially children – drew reactions from each side of the aisle.

In a post on his social networking site, Truth Social, Trump called her comments “nasty in tone” and remarked that she “brought her church into the World of politics in a really ungracious way.”

“She and her church owe the general public an apology!,” he posted. Several conservatives criticized her sermon, while many progressives saw her as “speaking truth to power.”

As a specialist in medieval Christianity, I used to be not surprised by the bishop’s words, as I do know that Christian history is stuffed with examples of people that have spoken out, unafraid to risk official censure, and even death.

Early voices

Even within the early centuries of Christianity, followers of Jesus Christ’s teachings could possibly be outspoken toward political leaders.

For example, within the first-century Gospels, John the Baptist, a recent of Jesus, confronts the ruler of Galilee, Herod Antipas, for marrying his brother’s wife – a practice forbidden within the Hebrew scriptures. For that, John the Baptist was ultimately beheaded.

In a prayer later called the Magnificat, Mary, the mother of Jesus, praises the glory and power of God who casts down the mighty and raises the lowly. In recent interpretations, these words have been understood as a call for those in authority to act more justly.

In the late fourth century – a time when Christianity had been made the official religion of the Roman Empire – a respected civil official named Ambrose became bishop of the imperial city of Milan in northern Italy. He became well-known for his preaching and theological treatises.

However, after imperial troops massacred innocent civilians within the Greek city of Thessaloniki, Ambrose reproached Emperor Theodosius and refused to confess him to church for worship until he did public penance for his or her deaths.

Ambrose’s writings on scripture and heresy, in addition to his hymns, had a profound influence on Western Christian theology; since his death, he has been venerated as a saint.

In the early sixth century, the Christian Roman senator and philosopher Boethius served as an official within the Roman court of the Germanic king of Italy, Theodoric. A respected figure for his learning and private integrity, Boethius was imprisoned on false charges after defending others from accusations by corrupt court officials acting out of greed or ambition.

During his time in prison, he wrote a philosophical volume in regards to the nature of what’s true good – “On the Consolation of Philosophy” – that’s studied even today. Boethius, who was executed in 524, is venerated as a saint and martyr in parts of Italy.

Thomas Becket and St. Catherine

One of essentially the most famous examples of a medieval bishop speaking truth to power is that of Thomas Becket, former chancellor – that’s, senior minister – of England within the twelfth century. On becoming archbishop of Canterbury, Becket resigned his secular office and opposed the efforts of King Henry II to bring the church under royal control.

Dukas/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

After living in exile in France for a time, Becket returned to England and was assassinated by a few of Henry’s knights. The king later did public penance for this at Becket’s tomb in Canterbury. Soon after, Becket was canonized a saint.

Another influential saint was the 14th-century Italian mystic and author Catherine of Siena. Because of the increasing power of the kings of France, the popes had moved their residence and offices from Rome to Avignon, on the French border. They remained there for a lot of the century, though this Avignon papacy increased tensions in western Europee.

Many Christian clerics and secular rulers in western Europe believed that the popes needed to return to Rome, to distance papal authority from French influence. Catherine herself even traveled to Avignon and stayed there for months, writing letters urging Pope Gregory XI to return to Rome and restore peace to Italy and the church – a goal the pope finally fulfilled in 1377.

Leaders speak up across denominations

The Reformation era of the sixteenth and early Seventeenth centuries led to the splitting of Western Christianity into several different denominations. However, many Christian leaders across denominations continued to lift their voices for justice.

One necessary and ongoing voice is that of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers. Early leaders, like Margaret Fell and George Fox, wrote letters to King Charles II of England within the mid-Seventeenth century, defending their beliefs, including pacifism, within the face of persecution.

In the 18th century, based on their belief within the equality of all human beings, Quaker leaders spoke in favor of the abolition of slavery in each the United Kingdom and the United States.

In fact, it was Bayard Rustin, a Black Quaker, who coined the phrase “to talk truth to power” within the mid-Twentieth century. He adhered to the Quaker commitment to nonviolence in social activism and was energetic for a long time within the American Civil Rights Movement. During the Montgomery bus boycott within the mid-Nineteen Fifties, he met and started working with Martin Luther King Jr., who was an ordained Baptist minister.

In Germany, leaders from various Christian denominations have also united to talk truth to power. During the rise of the Nazis within the Thirties, several pastors and theologians joined forces to withstand the influence of Nazi doctrine over German Protestant churches.

Their statement, the Barmen Declaration, emphasized that Christians were answerable to God, not the state. These leaders – the Confessing Church – continued to withstand Nazi attempts to create a German Church.

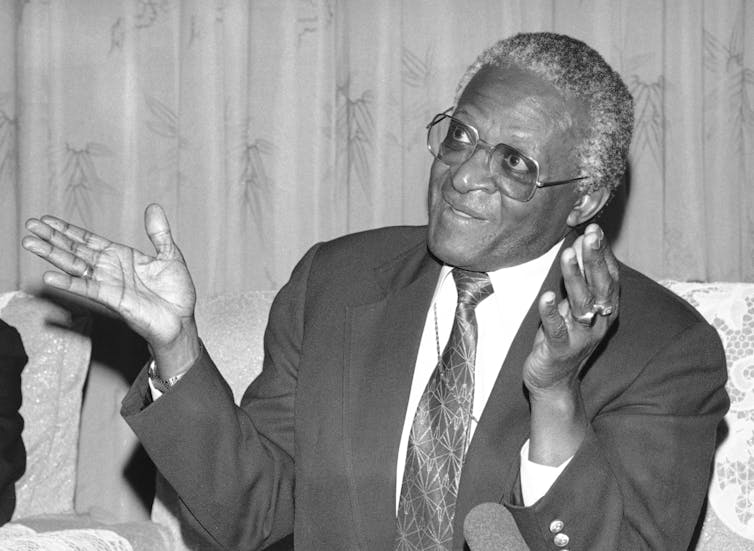

Desmond Tutu and other leaders

AP Photo/Jim Abrams

Christians on other continents, too, continued this vocal tradition. Óscar Romero, the Roman Catholic archbishop of San Salvador, preached radio sermons criticizing the federal government and military for violence and oppression of the poor in El Salvador during a national civil war. As a result, he was assassinated while celebrating Mass in 1980. Romero was canonized a saint by Pope Francis in 2018.

In South Africa, the Anglican bishop Desmond Tutu, archbishop of Cape Town, spent much of his energetic ministry condemning the violence of apartheid in his native country. After the tip of the apartheid regime, Tutu also served as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established to analyze acts of violence committed each by government forces and violent activists. Before his death in 2021, Tutu continued to talk out against other international acts of oppression. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

For some, Bishop Budde’s words might sound radical, rude, inappropriate or offensive. But she didn’t speak in isolation; she is surrounded by a cloud of witnesses within the Christian tradition of speaking truth to power.