On Dec. 31, while many persons are preparing for his or her New Years Eve parties, some Roman Catholic Christians may even mark the feast day for St. Silvester.

Little is thought for certain about Silvester’s life, but he lived during a transformational period within the history of Christianity. From 314-335 C.E., Silvester was the bishop of Rome: what we now call the pope, although the role was not so powerful on the time. “Pope” comes from the Greek word for “father,” and was widely utilized by bishops until the fifth century, when the bishop of Rome began to monopolize the title.

Silvester’s era was certainly one of each turmoil and transition for Christians living within the Roman Empire, as some Christian communities emerged from persecution into a robust alliance with the Roman state. His story is deeply intertwined with this alliance, which might fundamentally change the trajectory of the movement initiated by the figure of Jesus of Nazareth three centuries earlier. Christianity would now grow to be the religion of kings, states and empires.

A change in fortune

Trustworthy details of Silvester’s life are hard to come back by. The “Liber Pontificalis,” a catalog of papal biographies that began to be compiled within the sixth century, tells us that he was from Rome and the son of an otherwise unknown man named Rufinus.

As a young man, Silvester lived through the persecutions initiated under certainly one of the co-emperors on the time, Diocletian, which began in 303 C.E. These persecutions continued for several years after Diocletian stepped down.

Though many individuals picture early Christians being continuously persecuted by the Roman state, historians doubt these claims. The persecutions that began under Diocletian, nonetheless, are an exception. During this era, the state expected Christians to sacrifice to the gods for the well-being of the empire, or face consequences – sometimes violent ones.

Titus Project via Wikimedia Commons

According to the Christian theologian Augustine, some Christians later accused Silvester of having “betrayed” his faith during this era. Silvester was accused of turning over Christian sacred books to the Roman authorities and making offerings to the Roman gods.

The persecution got here to an end in 313, when the co-emperors Constantine and Licinius signed the Edict of Milan, which granted tolerance to Christianity within the empire. Just a yr later, Silvester became the bishop of Rome.

Constantine quickly became a serious patron of Christians, though the extent to which he practiced Christianity is debated. With imperial support got here an enormous Christian constructing campaign in Rome – a lot so that almost all of Silvester’s biography within the “Liber Pontificalis” consists of lists of all of the churches that Constantine gifted to the town.

Christian controversies

Both before and through Silvester’s time because the bishop of Rome, there have been many different Christianities within the empire. This diversity was troubling to Constantine, who wanted to advertise unity and order in his domain. As such, he began to convene councils of Christian clergy to sort out contentious issues.

In 314, the yr that Silvester became bishop, the emperor called the Council of Arles to deal with a dispute that had arisen amongst African bishops – what has grow to be often known as the Donatist Controversy. At issue was whether a priest who had betrayed his faith throughout the persecutions retained a legitimate ordination.

Silvester, though the bishop of a vital city, didn’t attend, but sent representatives in his stead. It could also be that, even at this early date, there have been already rumors about what Silvester might need done throughout the persecutions.

Jjensen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Around 10 years later, shortly after Constantine had grow to be the only ruler of the Roman world, he called one other council in Nicaea, in modern-day Turkey. This time, he wanted Christian leaders to deal with an emerging rift centered on the ministry of a charismatic cleric named Arius. Silvester didn’t attend this council either, but again sent representatives.

The council eventually adopted what has been called the Nicene Creed, a press release of religion that continues to be essential for a lot of modern Christians. However, the council didn’t resolve the split around Arius. In fact, Constantine would later be baptized by a supporter of Arius, Eusebius of Nicomedia.

These many years when Silvester presided over the church transformed Christianity from a persecuted group into allies of the state. This alliance made theological differences between Christians much more fraught, for the reason that force of the empire might now be wielded against one’s foes.

Rewriting history

But why, given these huge shifts, was Silvester not seen as a serious player within the politics of his day?

This was an issue that dogged later Christians – actually, they invented stories about Silvester that put him right in the middle of the motion.

In the fifth century, an anonymous writer wrote a biography now often known as the “Acts of Silvester,” which made Silvester seem central to Constantine’s conversion to Christianity.

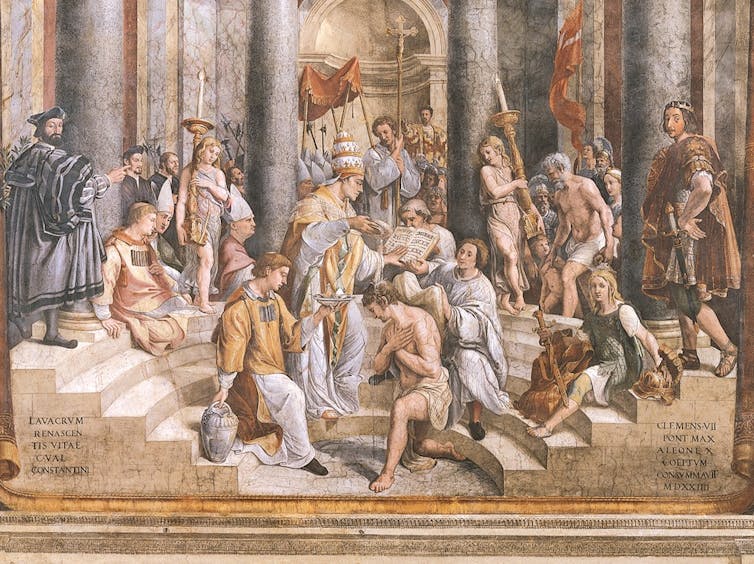

In the Acts, Constantine starts as a persecutor of Christians, for which God curses him with leprosy. Silvester, who had been in exile on a mountain near Rome amid the persecutions, is recalled to the town after Saints Peter and Paul visit Constantine in a dream. Silvester hears Constantine’s confession of religion, cures him miraculously of his leprosy, after which baptizes the emperor.

Just like that, Constantine now had a correct baptism from an orthodox bishop, not an Arian heretic.

Vatican Museums via Wikimedia Commons

A century later, the “Liber Pontificalis” would claim that it was Silvester, not Constantine, who called the Councils of Arles and Nicaea. The text also credited him with a series of legal rulings. These changes to Silvester’s story elevated him to a serious player within the events of his day. They also supported a growing effort to take a position the bishop of Rome with the form of authority that modern popes hold.

Donations and dragons

Legends about Silvester only grew with time – and even include a battle with a demonic dragon. But perhaps probably the most infamous legacy of Silvester is connected to the so-called “Donation of Constantine.”

This forged document was first drafted within the eighth century C.E. The Donation states that Emperor Constantine had bequeathed to the Roman bishop – on the time Silvester – control of the town of Rome, the western Roman Empire, huge tracts of land under imperial control, and authority over churches in the opposite centers of the Christian world, Constantinople.

For centuries, this document would undergird papal claims to each ecclesial and civil power. In the fifteenth century, German cardinal Nicholas of Cusa and the Italian scholar Lorenzo Valla showed the Donation to be a forgery, but by that time popes had already amassed the authority and wealth now related to the office.

Peter1936F/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Though the precise details of Silvester’s life will likely remain a mystery, the times he lived in were pivotal for the history of Christianity and the West. While he was bishop, Christianity took its first steps toward a longstanding alliance with imperial and state power. Over time, Silvester’s story was embellished to not only justify this alliance, but to argue that the church must have political power.

Today a robust block of Christian nationalists within the United States seeks similar power. For some, inspiration for this political project relies on the thought of a natural alliance between church and state – starting with Constantine, but justified by traditions invented across the lifetime of Silvester. Yet this alliance was an accident of history, not foreordained. Over time Christians within the Roman Empire invented reasons for why the church should align with the state – and, eventually, grow to be the state.