In the medieval church, women’s roles were limited – often some type of enclosure and celibacy, reminiscent of becoming an anchoress walled up alone for all times, or a nun in a classic convent. On the opposite extreme were just a few dramatic examples of girls who made history for the church while flying within the face of gender norms: heroes reminiscent of Joan of Arc.

The full truth, though, is more complicated. Medieval women were there all along, even in priests’ own houses. In her book “The Manly Priest,” historian Jennifer Thibodeaux reminds us that while celibacy was at all times the church’s ideal, it was not truly enforced until later within the Middle Ages. At least until the eleventh century, some priests had wives and youngsters who weren’t considered illegitimate. Even after the 14th-century Black Death, clerical households with wives and youngsters thrived in Italy.

As the church’s notions of illicit sex and illegitimacy hardened, nevertheless, its attitudes toward women did, too. Medieval scholars – all men – defined women’s temperament in negative terms: Women were libidinous, frivolous, unfaithful, capricious, unpredictable and simply tempted. They required constant surveillance and were evaded clerics, a minimum of in theory. They definitely couldn’t hold overt positions within the pope’s court unless they were his mother or sister.

Still, one other reality emerges. The church may not have seen women as equals, but nevertheless, their work was key to the workings and funds of the papal court and its surroundings. The fact is made obvious within the archives by simply following the cash. It was hardly glamorous work but needed for the functioning of the papal court.

Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal via Wikimedia Commons

Vatican payroll

The Vatican Archives’ account registers make it possible to trace who was paid and for what on the medieval papal court in Avignon, where the papacy was based for a lot of the 14th century. Amid the tedious task of deciphering various medieval shorthand systems, which organize expenses into categories reminiscent of “extraordinary wages,” “liturgical ornaments,” “war expenses” or “wax account,” I encountered surprises: Women appear within the lists of salaried employees on the medieval papal court.

Furthermore, they were involved in tasks that “touched” the leader of the church. Even a pope’s clothes need making, mending and washing. Women crafted an ornate style highly appreciated by the pontiffs – glorifying them with pure white linen and gold embroidery. The Vatican Apostolic Archives’ Introitus and Exitus, medieval financial records, provide substantial evidence that ladies made sacerdotal ornaments and garments.

Between 1364-1374, the registers recorded the pope’s launderesses – women otherwise lost to history. Among them were Katherine, the wife of 1 Guillaume Bertrand; Bertrande of St. Spirit, who washed all of the papal linens upon his election; and Alasacie de la Meynia, the wife of Peter Mathei, who did the pope’s laundry for the Christmas festivities of 1373 and is mentioned again in 1375.

These women were all wives of officers on the papal court. Records identified them by their full name, which was not the case for everybody on the pope’s payroll. This is essential: The records gave them real presence, unlike most female laborers.

Heidelberg University Library

Later records were less clear. Between the 1380s and 1410s, liturgical garments were made and washed by various women, including the unnamed wife of Peter Bertrand, a health care provider of law; Agnes, wife of Master Francis Ribalta, a physician of the pope; one other Alasacie, wife of carpenter John Beulayga; and the unnamed wife of the pope’s head cook, Guido de Vallenbrugenti – alias Brucho.

Only one woman, Marie Quigi Fernandi Sanci de Turre, appears and not using a male family member. As time progressed, women’s names weren’t systematically recorded.

Most of those later women, too, were married to curial officers who maintained rank at court by working in trade, medicine or the military. Women were never paid directly; their husbands collected their salaries. Still, this was not “unseen” labor but a salaried occupation, explicitly recorded.

Bibliothèque Nationale via Wikimedia Commons

Working day – and night

Many other women immigrated to work in Avignon. According to a partial survey of town’s heads of households in 1371, about 15% were women. Most had traveled far and wide – from elsewhere in present-day France, in addition to Germany and Italy – to achieve the papal court and a probability at employment.

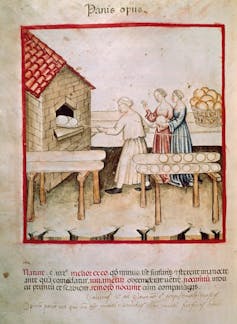

Of the whole female heads of household, 20% declared an occupation. The range of those women’s trades is staggering. There were fruit-sellers, tailoresses, tavern-keepers, butchers, candlemakers, carpenters and stonecutters. Women in Avignon worked as fish-sellers, goldsmiths, glove-makers, pastry-bakers, spice merchants and chicken-sellers. They were sword-makers, furriers, booksellers, bread-resellers and bath-keepers.

De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images

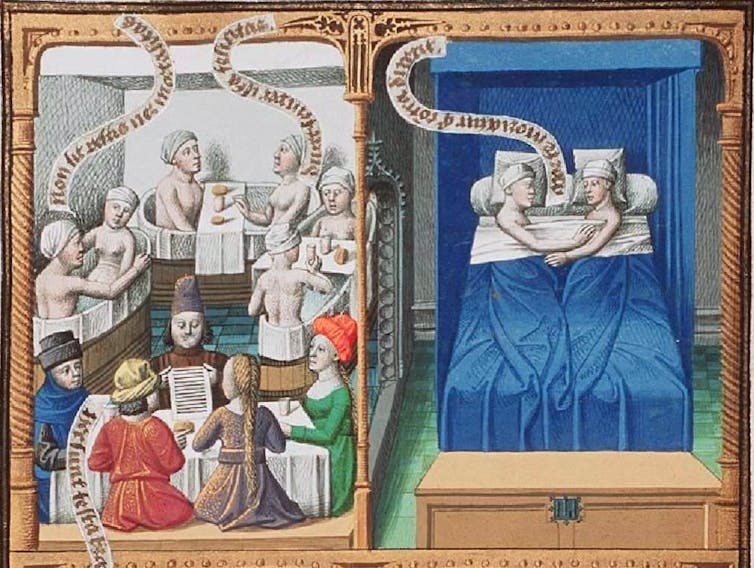

Bathhouses, the “stews,” were often brothels. Prostitution was considered a legal occupation in Avignon and controlled by the church. Marguerite de Porcelude, generally known as “the Huntress,” paid an annual tax to the diocese for her lodging. Several prostitutes rented tenements from the convent of St. Catherine, and Marguerite Busaffi, daughter of a outstanding banker, owned a brothel in town.

In 1337, the marshal of the Roman court – the best secular judicial officer – taxed prostitutes and procurers two sols per week. Pope Innocent VI, scandalized by the practice, annulled it in 1358.

Still, due to the overall taint related to the sex trade, the church attempted to reform prostitutes and convert them into nuns. The Avignon popes locked them up in a special convent, the Repenties, arrange removed from the middle of town.

National Library of the Netherlands via Wikimedia Commons

Eventually, the establishment became a type of prison for “unruly” women – those that were pregnant out of wedlock. But for some hundred years, groups of girls of the night took vows and lived as nuns there, controlling the affairs of their very own convent with an iron fist.

In the 1370s, Pope Gregory XI offered the nuns and their donors a plenary indulgence, a forgiveness of sins. They followed a rule emphasizing that no matter their pasts, abstinence and continence could make them spiritually “chaste.”

The ladies of the convent left detailed records of the properties they acquired. In 1384, its leaders petitioned the papal treasury, demanding arrears they were owed from a priest’s donation – and received what was due. Few medieval women had the chutzpah to petition a court for past dues, much less the pope’s. The Repenties did.