Why pray alone or together with your family when you can pray with big-biceped celebrities on the Hallow app? Why limit yourself to reading or hearing the Gospels when you can have a Jesus with all the fun and appeal of a bingeable Netflix series? Why cultivate the Ignatian prayer skill of energetic imagination when you may passively experience an immersive exhibit that brings a storm on the Sea of Galilee to life?

Why be satisfied with an bizarre church when you may digitally tour Europe’s biggest cathedrals or hearken to famous preachers comfortably at home? Or why accept traditional depictions of Jesus or figures from the Bible and church history when images of what The Atlantic dubbed “hot AI Jesus” and hot AI saints now proliferate online?

These are but among the questions posed by our digital era’s dizzying accelerations, and Christians best have a solution. Here, I’ll give attention to the bogus intelligence renderings of Jesus and explore how the instance of history’s biggest Christian artist, Michelangelo, can assist us resist the temptations of artificial devotion.

The easiest response to AI Jesus is to say that the iconoclasts—the Christian icon-breakers who warned against or outright destroyed devotional images in eighth-century Byzantium and sixteenth-century Europe—have been vindicated ultimately. An AI-generated image like shrimp Jesus is definitely enough to cause some to hope that a contemporary equivalent of Oliver Cromwell’s stained glass–smashing soldiers will soon ride again.

Modern iconoclasts would argue that churches must be clean and imageless, an ever more needed weekly cleansing of our digitally exhausted visual palette. This is venerable and ancient counsel. “When you might be praying,” wrote the fourth-century desert father Evagrius of Pontus, “don’t fancy the Divinity like some image formed inside yourself. Avoid also allowing your spirit to be impressed with the seal of some particular shape, but fairly, free from all matter, draw near to the immaterial Being and you may attain to understanding.” In other words, delete the app.

Image: AI-Generated Image by CT / Midjourney / Facebook

CT created hot AI Jesus (left) inspired by the social media trend on Facebook (right).

Another answer—from the iconophile, or image-loving one—would embrace these recent developments wholeheartedly, channeling them to positive effect. Arguably, this was Michelangelo’s approach. As his profession began, visually arresting classical sculptures were being dug up from the bottom, prompting in lots of a crisis of religion: Had Christianity brought such visual splendor to a premature end?

Michelangelo’s early sculptures answered with a convincing no, showing that Christian art could possibly be just as beautiful as that of the classical world, or much more so. Perhaps, we should always take an analogous approach to the brand new medium of AI, each embracing and exceeding what the world offers us today.

I tried that strategy myself, spending months using AI attempting to resurrect a lost African saint in AI-generated icons. It left me cold. Truth be told, the strategy of total embrace left Michelangelo cold as well. “So the affectionate fantasy, that made art an idol and sovereign to me,” he wrote in a late sonnet within the 1550s, “I now clearly see was laden with error, like all things men want regardless of their best interests.”

Image: WikiMedia Commons

The classical statue of Laocoön, unearthed in 1506, and one example of Michelangelo’s alluring Christian responses, Cristo della Minerva (1519–1521).

But that disillusion with cultural production doesn’t necessarily mean the iconoclasts win the argument. Michelangelo didn’t quit art completely. He as an alternative returned with recent intensity to a lifelong interest within the simpler and purer aesthetic of ancient Christian icons, which on several occasions he attempted to duplicate or echo. One art historian convincingly argues that Michelangelo aimed to “preserve traditions of spiritual imagery at a time when artistic developments threatened their integrity and dominance,” and that—I feel—must also be our strategy today.

Michelangelo also actively undermined the visual techniques he had mastered. Influenced by Reformation doctrines of grace, Michelangelo’s last works are deliberately impoverished. You can see this shift within the contrast between his first and more famous Pietà, made when he was in his early 20s, and the Rondanini Pietà, executed when he was in his 80s. In the primary, a bigger than life, impossibly youthful Mary holds Jesus; within the deliberately rough and unfinished second, Jesus—even in his death—appears to be upholding the appropriately aged Mary.

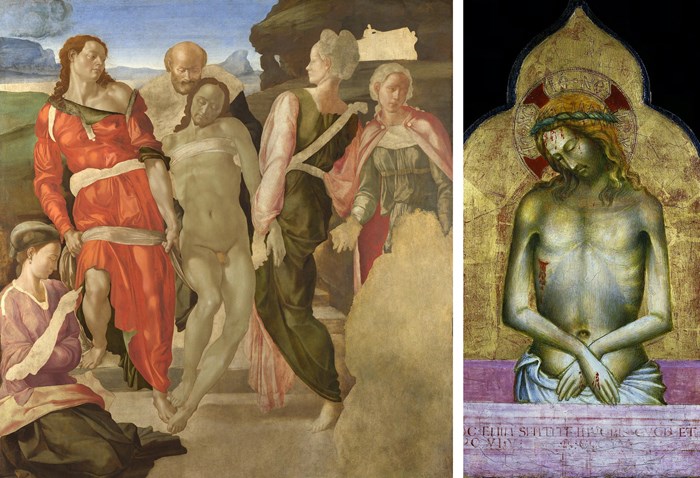

Image: WikiMedia Commons

Michelangelo’s Entombment (1500–1501) and the common-or-garden ancient icon (1405) that helped encourage it.

Michelangelo’s trust in ancient, humbler art forms and his deliberate embrace of visual poverty helped him navigate the tumultuous sixteenth century, and it might help us navigate our own time as well. Deluged with AI’s slick and sexually suggestive images of Jesus, we will profit from the wisdom of faithful iconoclasts without abandoning devotional images completely.

Like Michelangelo, we will decide to make and contemplate Christian images which can be humble, perhaps unimpressive but deliberately and faithfully so. We can seek art that doesn’t dazzle our earthly senses but defers to heavenly realities. Owing to the actual fact that the present “data sets these [AI] tools are trained on are biased toward hotness,” the brand new tools are unlikely to assist. We do higher to embrace images that pronounce their poverty, images that say, like John the Baptist, “He must increase, but I have to decrease” (John 3:30, KJV).

Michelangelo’s example teaches us to be suspicious of concocted visual greatness. Even if machines can now sculpt in addition to he could, the lesson of Michelangelo’s final years stays the identical: Christian images, insofar as they deserve the name Christian, must be deliberately restrained, for his or her purpose is just not to draw attention or glory but to show our eyes toward Christ. The traditional canon of Orthodox icons, more cost-effective now than ever, still does this remarkably well.

Image: WikiMedia Commons

Michelangelo’s early Pietà (1498–99) and his late Rondanini Pietà (1564).

Faced with its own bewildering array of eloquent preachers and visually immersive pagan shrines, the traditional church asked questions just like the ones with which I started. The apostle Paul’s answer was candid, even blunt: “I didn’t include eloquence or human wisdom as I proclaimed to you the testimony about God,” he wrote to the Corinthian church. “For I resolved to know nothing while I used to be with you except Jesus Christ and him crucified. I got here to you in weakness” (1 Cor. 2:1–3).

In this and the testimony of Michelangelo, then, I see a straightforward rule for sifting this fresh round of visual enchantments: Never trust a picture—or a savior—without wounds.

Matthew J. Milliner is a professor of art history at Wheaton College. He is writer most recently of Mother of the Lamb: The Story of a Global Icon.