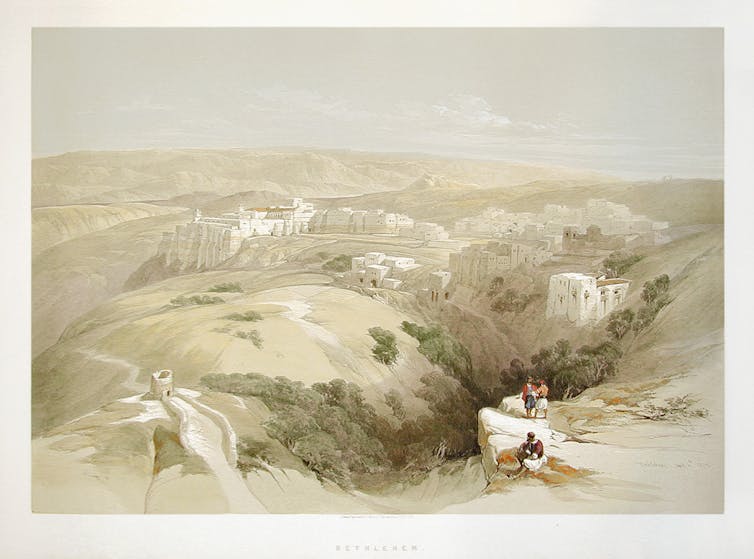

Every Christmas, Bethlehem becomes a spotlight of worldwide attention because the scene of the Nativity – the birth of Christ. In most years, the town’s centre is crowded with Christian pilgrims. Indeed, many individuals travel to the Holy Land all year long to go to places of non secular importance – whether in Jerusalem, Nazareth or across the Sea of Galilee.

But when did Christians start to contemplate places as holy and start travelling to them on pilgrimage? Following on from my archaeological work in Nazareth, I made a decision to analyze using each ancient written sources and archaeological evidence.

According to the gospels, Christ taught that there was no such thing as a “holy place”. But by the third century, distinguished Christians equivalent to Alexander, later bishop of Jerusalem, and the renowned scholar Origen of Alexandria, were looking for out locations mentioned within the Bible. Even earlier, within the mid-second century, the Christian author Justin Martyr knew of a cave in Bethlehem said to be the situation of the Nativity.

The Gospel of James, sometimes called the Protoevangelium of James – which dates from the second century – also mentions such a cave at Bethlehem. While these writers could possibly be referring to different caves, they attest that Bethlehem had at the least one Christian holy place inside a generation or two of the composition of the Gospel of John, the last of the canonical gospels.

Written sources show other Christian holy places at a similarly early date. A cave on the Mount of Olives, just outside ancient Jerusalem, was assigned Christian significance within the Apocryphyal Acts of John, probably written within the late second century. Inside Jerusalem itself, the first-century tomb later revered because the place of Christ’s burial and of the Resurrection (the Holy Sepulchre) could have already been identified as such within the second century.

Ken Dark, Author provided (no reuse)

The fourth-century historian Eusebius says that Hadrian built a temple over the tomb in opposition to its Christian significance and – as Hadrian built temples at, or near, each the Jewish temple at Jerusalem and a very powerful Samaritan shrine at Mount Gerizim – this may increasingly be greater than late Roman speculation. Eusebius’s account can be consistent with archaeological evidence for a monumental Roman constructing on the Holy Sepulchre site later than the first-century tomb and before the fourth-century pilgrimage church there (the Church of the Holy Sepulchre).

Seven other fourth-century pilgrimage churches were on sites with caves at the least partly cut out of the rock fairly than being wholly natural caverns. As well because the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem, where Jesus was born, these included churches at: Shepherds’ Field(s), a location just outside Bethlehem where the angels were believed to have announced Christ’s birth; the “Eleona” (olive grove) church on the Mount of Olives, a site related to the Ascension when Christ returned to Heaven; Gethsemane, where Jesus was betrayed by Judas; and Tabgha by the Sea of Galilee, near what was believed to be the positioning of the Sermon on the Mount. There were also two at Nazareth, related to the Annunciation – the announcement to Mary by the angel – and with Jesus’ childhood home.

All these fourth-century churches were either situated in reference to, or were actually inside, the caves. These caves were subsequently probably understood as marking the locations of the events related to their sites within the fourth century.

For example, at Bethlehem, the early fourth-century Church of the Nativity was specifically designed to display the cave as the first physical focus of the church, and the altar was situated within the cave itself. On archaeological grounds alone, the most effective interpretation of this layout is that the church and its altar were positioned due to pre-existing religious importance of the cave.

Author provided

This interpretation of the caves typically is supported by written evidence. Eusebius wrote in his Life of Constantine that three great imperial churches were in-built the early fourth century at places where crucial moments within the Gospels took place: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; the Church of the Nativity; and the “Eleona”. All of those buildings, Eusebius says in his famous Ecclesiastical History, were built over pre-existing “caves” – one actually a rock-cut tomb – related to the events commemorated by their fourth-century churches.

Pilgrimage trail

If at the least a few of the caves at these seven sites were constructed or modified to point places of Christian significance prior to the fourth century, they’re among the many earliest specifically Christian structures yet known. But nothing about them suggests there have been greater than a couple of local people involved of their construction, and the numerous details of their size and plan suggest they’re the products of separate initiatives.

The use of the caves in this fashion may imply that they were visited for religious reasons sooner than their fourth-century churches – perhaps the earliest type of Christian pilgrimage. If the events commemorated by them were similar to the dedications of their later churches, then they’d form a narrative sequence from the Annunciation to the Resurrection, with each cave (and the tomb on the Holy Sepulchre site) related to just one event. It is subsequently possible that, even before these sites were used for fourth-century churches, Christians travelled between them in a sequence following the order of those events within the Gospels.

This means written and archaeological evidence suggest that the origins of Christian topography and pilgrimage were sooner than normally supposed. If so, the fourth-century imperial church-builders inherited – fairly than created – a network of holy places that had probably been emerging progressively over centuries as a consequence of small-scale local, and maybe low-status, initiatives.