Nearly 60 years ago, in October 1962, Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council. For the twenty first time within the Catholic Church’s history, the pope gathered bishops from all over the world – several thousand of them – to handle matters of church doctrine and practice.

Today, Vatican II is remembered as a landmark council that has shaped Catholic life in modern times. Leaders agreed to reforms, reminiscent of greater use of local languages within the Mass, to reinvigorate the church’s mission in a changing world.

In the council’s official documents, nevertheless, the bishops regularly cite spiritual guides who died greater than 1,000 years before: the fathers of the church.

The spiritual and theological authority of the fathers is recognized not only by Catholics, but in addition by other Christians, including Eastern Orthodox and Protestant communities. Not all agree on the identical list of church fathers, yet Christian leaders have been deeply influenced by the fathers’ teachings, from medieval theologians and Protestant reformers to Pope Francis today.

And while there aren’t any women among the many “fathers,” the “desert moms” – influential religious women from the identical era – have also left their mark.

Spiritual fathers

As a scholar of early Christianity, I’m often asked concerning the origins of the concept of a church father.

In Christianity, the honorary title “father” comes from Greco-Roman and biblical ideas concerning the father as the pinnacle of the family. The Roman “pater familias” was answerable for the welfare, education and leadership of the family. He was also considered a priest or religious representative of the household.

In the Bible, the first-century Apostle Paul speaks of himself as a spiritual father to other Christians. The apostles and bishops of the church were treated as believers’ “fathers” insofar as they were answerable for preaching, teaching and leading worship.

Evolving idea

Early Christians began using the title “father” for bishops, but by the fifth century, it was also applied to some priests and deacons.

Over time, theologians began to discuss with a particular group of “church fathers” to support their positions amid debate – starting within the fourth century, with the Greek bishops Eusebius, who wrote a history of the Christian church’s first three centuries, and Basil of Caesarea, who lived in what’s now Turkey. St. Augustine – the Catholic bishop in Roman North Africa who became famous for his “Confessions” – regularly cited the fathers’ teachings to support his arguments during controversies with theological opponents.

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The fathers’ position within the church was refined within the fifth century by a Gallic monk named Vincent of Lérins. Not all ancient Christian writers had equal authority, he wrote, however the views of the true fathers could possibly be trusted because their teachings were consistent, as in the event that they formed a council of masters “all receiving, holding and handing on the identical doctrine.”

By the fashionable era, 4 traits were used as criteria to differentiate fathers of the church: 1) orthodox or right theological teachings on essential points, in accord with the church’s public doctrine; 2) the holiness of their life; 3) the church’s recognition of them and their teaching; and 4) antiquity, meaning they lived through the early Christian era that ended across the seventh or eighth century.

The title is distinct from the later honorific “doctor of the church,” for spiritual teachers who’ve made significant contributions to Christian doctrine in any period of history, although some theologians hold each titles.

Unlike the fathers of the church, who’re all male, 4 women are included among the many doctors: Teresa of Ávila, a mystic famous for ecstatic visions; Catherine of Siena, who persuaded Pope Gregory XI to return the papacy to Rome from Avignon; Thérèse of Lisieux, known for her “little way” of holiness by small acts of affection; and Hildegard of Bingen, a medieval German nun, scientist and composer.

Desert moms

Modern scholarship has also drawn attention to the essential influence of girls on the church through the age of the fathers.

For example, the fourth-century fathers Basil and Gregory of Nyssa, who were brothers, considered their older sister, Macrina the Younger, to be the best theologian amongst them. Gregory composed a treatise in her honor, “The Life of Macrina,” which depicts her as a real philosopher. A “consecrated virgin” who pledged her life to the church as a substitute of marriage and family, Macrina led a women’s religious community and was renowned for her holiness, teaching and miraculous healings.

Her paternal grandmother, Macrina the Elder, was also an important teacher and leader who suffered persecution for being a Christian within the late third century. She was answerable for passing on the teachings of essential theologians, reminiscent of Origen of Alexandria and “Gregory the Miracle-Worker.”

In addition, women exercised leadership in the growing movement generally known as monasticism. During the primary five centuries of Christianity, many ladies fled from urban cities to the desert to commit themselves to lives of prayer, fasting and virtue. Known because the “desert moms,” they were wanted for his or her wisdom.

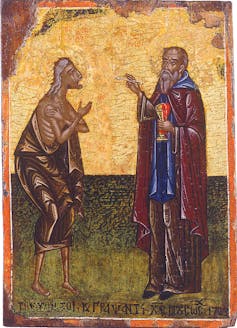

Heritage Images/Hulton Fine Art Collection via Getty Images

Their words or sayings were collected and preserved for hundreds of years. For example, Amma Theodora, a spiritual mother of a community of girls near Alexandria in Egypt, was famous for saying that only humility, not ascetical practices reminiscent of fasting, could overcome the temptations of the devil. Likewise, “The Life of Mary of Egypt” was written about a humble, penitent woman who lived within the desert for 47 years. She was considered a model of humility, and her story was often told during Lent, a period when many Christians perform penitential practices.

The fathers’ future

Today, church leaders proceed to depend on the fathers’ teachings as authoritative sources of wisdom. Pope Francis, for example, often refers to Vincent of Lérins to clarify how Christian doctrine develops over time, like a seed taking root and growing right into a tree.

History has shown that Christians regularly disagree on matters of doctrine, they usually all the time will. In those moments, future leaders may look to the fathers as sure-footed spiritual guides.