As someone who researches slavery in the traditional Mediterranean world, especially within the Bible, I often hear remarks like, “Slavery was totally different back then, right?” “Well, it couldn’t have been that bad.” “Couldn’t slaves buy their freedom?”

Most people within the United States or Europe within the twenty first century are more knowledgeable concerning the transatlantic slave trade, and live in societies deeply shaped by it. People can see the consequences of contemporary enslavement in all places from mass incarceration and housing segregation to voting habits.

The effects of ancient slavery, alternatively, aren’t as tangible today – and most Americans have only a vague idea of what it looked like. Some people might consider biblical stories, reminiscent of Joseph’s jealous brothers selling him into slavery. Others might picture movies like “Spartacus,” or the parable that enslaved people built the Egyptian pyramids.

Because these sorts of slavery took place so way back and weren’t based on modern racism, some people have the impression that they weren’t as harsh or violent. That impression makes room for public figures like Christian theologian and analytic philosopher William Lane Craig to argue that ancient slavery was actually helpful for enslaved people.

Modern aspects like capitalism and racist pseudoscience did shape the transatlantic slave trade in uniquely harrowing and enduring ways. Enslaved labor, for instance, shaped economists’ theories concerning the “free market” and global trade.

But to grasp slavery from that era – or to combat slavery today – we also need to grasp the longer history of involuntary labor. As a scholar of ancient slavery and early Christian history, I often encounter three myths that stand in the way in which of understanding ancient slavery and the way systems of enslavement have evolved over time.

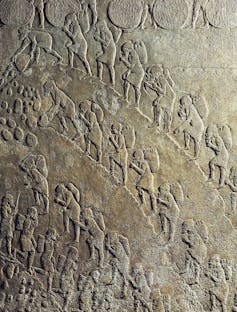

Werner Forman/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Myth #1: There is one sort of ‘biblical slavery’

The collection of texts that ended up within the Bible represent centuries of various writers from across the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia, often in very different circumstances, making it hard to generalize about how slavery worked in “biblical” societies. Most importantly, the Hebrew Bible – what Christians call “the Old Testament” – emerged primarily in the traditional Near East, while the New Testament emerged within the early Roman Empire.

Forms of enslavement and involuntary labor in the traditional Near East, for instance – areas reminiscent of Egypt, Syria and Iran – weren’t at all times chattel slavery, during which enslaved people were considered property. Rather, some people were temporarily enslaved to repay their debts.

However, this was not the case for all people enslaved in the traditional Near East, and definitely not under the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire, where hundreds of thousands were trafficked and compelled to labor in domestic, urban and agricultural settings.

Because of the range of periods and cultures involved within the production of biblical literature, there isn’t a such thing as a single “biblical slavery.”

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Nor is there a single “biblical perspective” on slavery. The most anyone can say is that no biblical texts or writers explicitly condemn the institution of enslavement or the practice of chattel slavery. More robust challenges to slavery by Christians began to emerge within the fourth century C.E., within the writings of figures like St. Gregory of Nyssa, a theologian who lived in Cappadocia, in present-day Turkey.

Myth #2: Ancient slavery was not as cruel

Like Myth #1, this myth often comes from conflating some Near Eastern and Egyptian practices of involuntary labor, reminiscent of debt slavery, with Greek and Roman chattel slavery. By specializing in other types of involuntary labor in specific ancient cultures, it is straightforward to overlook the widespread practice of chattel slavery and its harshness.

DEA/A. Dagli Orti/De Agostini via Getty Images

However, across the traditional Mediterranean, there may be evidence of a wide range of horrific practices: branding, whipping, bodily disfiguration, sexual assault, torture during legal trials, incarceration, crucifixion and more. In fact, a Latin inscription from Puteoli, an ancient city near Naples, Italy, recounts what enslavers could pay undertakers to whip or crucify enslaved people.

Christians weren’t exempt from participating on this cruelty. Archaeologists have found collars from Italy and North Africa that enslavers placed upon their enslaved people, offering a price for his or her return in the event that they fled. Some of those collars bear Christian symbols just like the chi-rho (☧), which mixes the primary two letters of Jesus’ name in Greek. One collar mentions that the enslaved person must be returned to their enslaver, “Felix the archdeacon.”

It’s difficult to use contemporary moral standards to earlier eras, not least societies hundreds of years ago. But even in an ancient world during which slavery was ever present, it is evident not everyone bought into the ideology of the elite enslavers. There are records of multiple slave rebellions in Greece and Italy – most famously, that of the escaped gladiator Spartacus.

Myth #3: Ancient slavery wasn’t discriminatory

Slavery in the traditional Mediterranean wasn’t based on race or skin color in the identical way because the transatlantic slave trade, but this doesn’t mean ancient systems of enslavement weren’t discriminatory.

DeAgostini/Getty Images

Much of the history of Greek and Roman slavery involves enslaving people from other groups: Athenians enslaving non-Athenians, Spartans enslaving non-Spartans, Romans enslaving non-Romans. Often captured or defeated through warfare, such enslaved people were either forcibly migrated to a recent area or were kept on their ancestral land and compelled to do farmwork or be domestic staff for his or her conquerors. Roman law required a slave’s “natio,” or fatherland, to be announced during auctions.

Ancient Mediterranean enslavers prioritized the acquisition of individuals from different parts of the world on account of stereotypes about their various characteristics. Varro, a scholar who wrote about the management of agriculture, argued that an enslaver shouldn’t have too many enslaved individuals who were from the identical nation or who could speak the identical language, because they could organize and rebel.

Ancient slavery still relied on categorizing some groups of individuals as “others,” treating them as if they were wholly different from those that enslaved them.

The picture of slavery that almost all Americans are conversant in was deeply shaped by its time, particularly modern racism and capitalism. But other types of slavery throughout human history were no less “real.” Understanding them and their causes may help challenge slavery today and in the long run – especially at a time when some politicians are again claiming transatlantic slavery actually benefited enslaved people.